Quinnipiac University Study

aided by the University of Saint Joseph School of Interdisciplinary Health and Science

Background

Based on these new insights my redesigned experiments yielded very quick results. The hamstring area injury healed in about a month. Expanding the techniques and methods to other areas, and developing a strategy, I was fortunate to have been able to develop a comprehensive system that resolved all my injuries, eliminated any pain and substantially increased my flexibility.

After applying this same system to help several other people I became convinced that it was universally applicable. But, I needed more then just anecdotal evidence. Professor Richard Feinn from Quinnipiac University came to the rescue. He allowed me to propose a study. Professor Fienn teamed up with Professor Karen Myrick to undertake the study. Prof. Myrick organized a team comprised of Matthew Williams, Jessica Lapinsky and, eventually, Professor Nicholas Nicholson. Prof. Myrick and Prof. Fienn guided the proposal through the necessary approvals.

The North Haven Health & Racquet club agreed to host the study. Fortunately, I have very dedicated and caring helpers, Will Bermender, Diane Jablonski and Scott Vonick who assisted me in carrying out our part of the work during the study.

Although Professor Myrick left Qunnipiac and joined the faculty of the University of Saint Joseph, she stayed with the Team to finish the study. She has been the lead in publicising the study, so we owe her many thanks.

Study Overview

The study measured the range of motion of the subjects in several key areas, based on established, known measuring techniques and metrics. The subjects also filled out questionnaires regarding the pain they experienced and other aspects of their quality-of-life, using known and accepted medical metrics.

The results of the study confirm that the Painless Flexibility™ system is effective in increasing flexibility and reducing/eliminating pain, particularly in the lumbar area, as well as improving the quality of life. This is a viable alternative treatment to the common lower back pain that afflicts many millions of Americans.

The study results have been presented on the following forums:

1.) Eastern Nursing Research Society, 32nd Annual Conference, in May 2020 (virtual presentation). Placed in Library.

2.) American College of Sports Medicine, on a virtual conference in May, 2020.

Abstract published in:Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise: Nicholson, Nicholas, Myrick, Karen, Lapinski, Jessica, Williams, Matthew, Nemeth, Laszlow & Feinn, Richard. (2020). Evaluation Of The Painless Stretching Program On Range Of Motion And Pain: 1572 Board #166 May 28 10:30 AM – 12:00 PM. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 52, 417. https://doi.org/10.1249/01.mss.0000678396.63339.84

Quinnipiac University Study Article

Back Pain Resolution Learned from Evolution

Impact Study of the Painless Flexibility™ system

Authors:

Laszlo Nemethc, Nicholas Nicholsona, Karen Myrickb, Richard Feinna.

- Quinnipiac University, Hamden, CT. Hamden, CT

- Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA

- North Haven Health & Racquet, 100 Elm Street, North Haven, CT 06473, USA

Abstract

Chronic lower back pain afflicts about 80% of adults in Western countries without a known cause or resolution. This pathology is absent in current hunter-gatherer tribes – living surrogates to our ancestors. Evolution, over millions of years, perfected humans to fit the hunter-gatherer lifestyle. The current, sedentary lifestyle is a sudden departure from the long evolutionary trajectory. Humans have not had the time to adapt to it via evolution. The mismatched lifestyle creates atrophy and distortion of the fascia, preventing it from distributing physical stress correctly. We hypothesize that this is the underlying cause of the common lower back pain. The Painless Flexibility™ system was created to restore the fascia functions closer to the evolutionary design, thereby resolving the underlying cause of the common lower back pain. Our study evaluated the efficacy of the Painless Flexibility™ system in a cohort of subjects living a sedentary lifestyle and suffering from lower back pain. The study results indicate that this system is an effective modality to resolve lower back pain. There was a statistically significant improvement in scapular retraction (d=1.25, p=.005), sit and reach (d=1.26, p=.005), spine rotation (d=1.39, p=.003), and modified Thompson test (d=1.58, p=.001). Reported pain decreased (d=0.74, p=.015).

Perspective

Recent discoveries of the critical functions of the fascia in human bio-mechanical, tensegrity structure suggest a plausible explanation of the cause of common lower back pain. Insights learned from human evolutionary history may hold the key to an effective and inexpensive resolution for millions of pain sufferers.

Introduction

Back pain is a severe health issue that is projected to affect up to 80% of adults in Western countries. Being the most common musculoskeletal pathology, it is of great concern that there is no appropriate intervention and most cases have no known cause.1 The Painless Flexibility™ system was designed to resolve the common back pain by addressing the underlying cause.

The underlying cause is postulated to be a life-style induced condition: Human evolution, through 2.5 million years, produced a creature that was well adapted to a hunter-gatherer life-style. Starting about 12 thousand years ago that life-style changed, first to an agricultural and later to a sedentary way of life. Human physiology has not adapted via evolution to this relatively rapid change. The theory posits this to be the underlying cause of common back pain cases and many other related conditions. The hypothesis postulates that the lack of adaptation can be overcome by an effective intervention. This hypothesis is supported by observations of current hunter-gatherer tribes that are studied extensively. They have no chronic ailments and retain their vitality undiminished throughout their life.2

The bio-mechanical functions associated with the cause of the common back pain, and its resolution, are the following: Recent research reveals that the fascia is the primary structure in humans that in conjunctions with the bones in a tensegrity arrangement, distributes physical stress.3,4 It also defines range of motion, shape and posture. It connects every bone and part, every cell in the human body in one, comprehensive, continuous structure. The fascia is dynamic and it configures itself into the most economical, minimum arrangement necessary to support daily activities. Thus, during a predominantly sedentary life, the fascia structure gradually changes to conform with the diminished requirements and concomitant, reduced range of motion of that life-style. This change creates progressively more distortion, atrophy and misalignment, out of balance with the rest of the physical structure that cannot adapt so readily. Hence, the structure as a whole becomes unable to distribute physical stress properly, leading to many symptoms, such as lower back pain, sciatica, and other related, painful conditions, as well as, increased susceptibility to injuries.5

The Painless Flexibility™ system was created to reverse the atrophy, misalignment and distortions by restoring the structure and mobility of the entire fascia closer to its original, evolutionary design, enabling it to function again in harmony with all other parts of the body to distribute physical stress properly. This intervention is stipulated to provide a resolution of the above stated symptoms.

The purpose of this study was to assess the efficacy of the Painless Flexibility™ system on pain reduction in a group of people suffering from lower back pain, using an 18 week intervention.

Methods

Subjects: A convenience sample of 9 adult subjects enrolled in the study to participate in the flexibility training program. The program was offered at a North Haven, Connecticut, fitness center and subjects had the option to take the program without participating in the data collection. All 9 persons who signed up for the program agreed to participate in the study and signed the consent form. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Quinnipiac University Institutional Review Board.

Participants or the public were not involved in the study’s conceptualization, design and conduct, and/or dissemination of the study results.

Intervention: The Painless Flexibility™ program was conducted once weekly for 18 weeks with each session lasting one hour. The program incorporated both static and dynamic flexibility exercises, most of which are unique to this system, and each week new exercises were added to expand the set of exercises to be practiced daily. Subjects were given access to a website that listed and demonstrated all the exercises performed in class, which they could use for reference. They were asked to perform the full set of exercises they have learned, each day for the subsequent week. The flexibility exercises encompassed the entire fascia structure of the body, including all muscles, with an emphasized focus on the fascia structure of the back and midsection.

Measures: Subjects completed a series of questionnaires at baseline, at midpoint then at the endpoint after the 18th week of the program. The questionnaires included the Global Pain Scale (GPS) and a question on current pain measured on a 10 point scale.

Additionally, subjects participated in a physical evaluation that included scapular retraction, sit and reach test, spine rotation pretzel while seated with extended contralateral leg and flexed lateral leg, supine spine hip, and the Thomas test of internal and external rotation. The physical evaluation took place at the same time points as the pain questionnaires.

For scapular retraction, the distance between the scapulae was measured at rest and with maximum scapular retraction effort. During the sit and reach test, the degree of trunk flexion was measured with a goniometer at the anatomical resting position of the hands as the subjects sat with their legs extended and reached. Spine rotation was measured using a goniometer as subjects were seated with one leg extended and the other leg bent. The Thompson Test measured knee flexion and hip flexion angles while the subjects lay supine with one knee flexed and hugged into the abdomen to maximum exertion while the other knee was extended.

Data Analysis: Descriptive statistics included means with standard deviations for quantitative variables and frequencies with percentages for qualitative variables. Linear Mixed Models was used to test for change across the three time points on the physical evaluation measures and pain scales. Time point was a fixed effect and the intercept was random and varied by subject. A significant effect for time point was followed by pairwise comparisons to determine specifically which time points differed. Analyses were conducted in SPSS v26 and statistical significance was set at an alpha level of .05.

Results

There were nine adult participants ranging from 30 to 78 years of age, of whom four (44%) were female. Six participants (67%) were measured at all three time points, while three (33%) were measured at baseline and midpoint but not endpoint. All nine participants reported lower back problems and the primary reason for enrolling in the program.

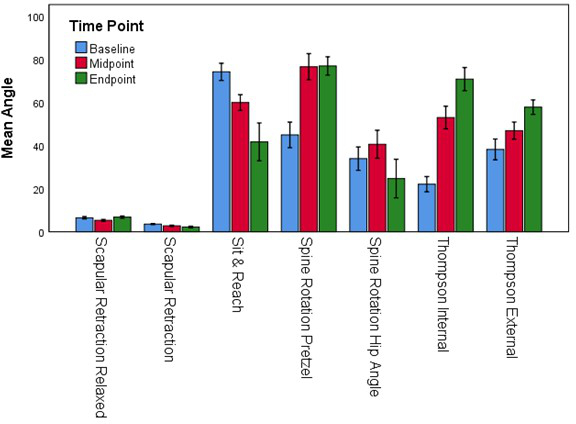

Table 1 and Figure 1 show the mean angle for each stretch at the three time points. There was a significant difference in scapular retraction with a smaller angle at midpoint compared to baseline and endpoint. For scapular retraction there was a significant difference resulting from a smaller angle at endpoint compared to baseline. There was a significant difference on sit & reach with a decreasing trend in angle with subsequent time points. For spine rotation pretzel there was a significant increase in range of motion from baseline to midpoint but not midpoint to endpoint. Spine rotation hip did not differ between time points. Both internal and external Thompson showed significant change between time points. All time points differed for internal with significant increases from baseline to midpoint and midpoint to endpoint. External increased across time points with a significant change from baseline to midpoint.

Table 1: Estimated means for each stretch at each time point

| Stretch |

Baseline |

Midpoint |

Endpoint |

P-Value |

| Scapular Retraction Relaxed |

6.50a |

5.31b |

6.70a |

.007 |

| Scapular Retraction |

3.56a |

2.75ab |

2.21b |

.017 |

| Sit and Reach |

74.11a |

59.89b |

41.98c |

<.001 |

| Spine Rotation Pretzel |

44.89a |

76.44b |

77.06b |

.001 |

| Spine Rotation Hip |

33.89 |

40.56 |

24.90 |

.284 |

| Thompson Internal |

22.06a |

52.94b |

70.97c |

<.001 |

| Thompson External |

38.17a |

46.89ab |

58.79b |

.017 |

Superscript with the same letter denote time points that did not differ while different letters denote significant difference

Figure 1: Mean (±SEM) angle by stretch and time point

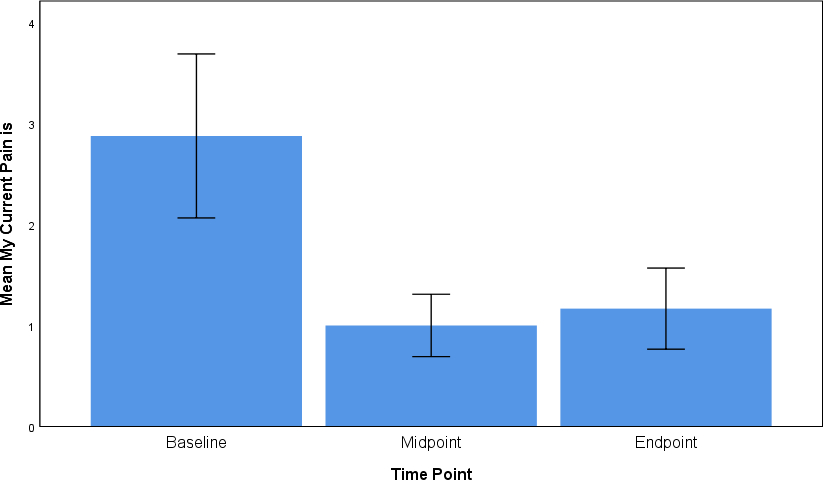

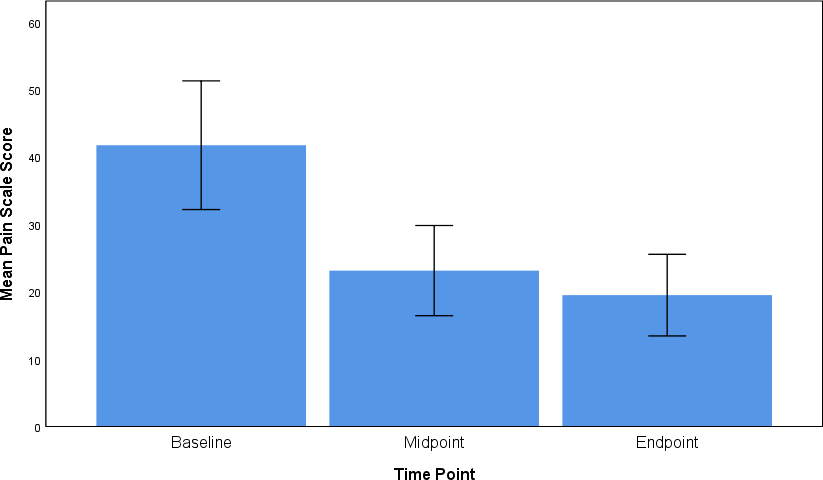

The mean values for current pain and global pain score are shown in Table 2 and Figures 2 & 3. For current pain participants reported significantly lower pain at midpoint and endpoint compared to baseline, with similar scores between midpoint and endpoint. Similarly, for total pain score there was a significant decrease from baseline to midpoint with similar levels between midpoint and endpoint.

Table 2: Estimated mean pain scores at each time point

| Measure |

Baseline |

Midpoint |

Endpoint |

P-Value |

| Current Pain |

2.88a |

0.93b |

1.08b |

.029 |

| Pain Score |

41.84a |

19.57b |

15.46b |

.016 |

Superscript with the same letter denote time points that did not differ while different letters denote significant difference

Figure 2: Mean (±SEM) for current pain question

Discussion

Our study showed greater flexibility of the subjects after participating in an 18-week program using the Painless Flexibility™ system and a significant reduction in reported pain. In support of the theory that the human fascia needs to be, and can be, “re-programmed” to counter our sedentary lifestyle, we found several key points. People came into the study with high levels of pain, and based on our study results, their mean pain score went down significantly. We believe the study strongly suggests a causal relationship between the increased flexibility gained from participation in the Painless Flexibility™ system training, and the reduction of pain.

At the conclusion of the study, participants were performing stretches they weren’t able to do before, pain-free. The sit and reach stretching activity showed significant improvement among participants. The degree of the angle between the participants’ chests and ankles gradually decreased as they practiced the exercises, indicating an increase in flexibility. The modified Thompson test showed statistically significant results, as well. Most participants were unable to rotate their hips during the initial measurements. By the end of the study, participants were able to rotate their hip past previous collections internally and externally.

Related studies

Other studies addressing the common back pain suggest the following three aspects might play a role in relieving back pain: Fascial layers, Hyaluronic acid, and Endorphins.

Aggressive stretching maneuvers are useful in the treatment of chronic low-back pain. Previous multi-modal rehabilitation programs with the addition of systemic stretching movements found an increase in functional abilities of subjects and their static strength of back extensors. Back muscle myoelectric signals and a decrease in back pain further suggested that stretching maneuvers enhance the functionality and comfort of patients.6

Hyaluronic acid is a natural substance found between the layers of fascial tissue. The primary function is lubrication and is essential to smooth movement, distribution of force, and comfort. Hyaluronic acid and its distribution are found to be proportionally related to both localized pain and stiffness. In response to a sedentary lifestyle, hyaluronic acid becomes stationary between layers and is not equally distributed. A sedentary lifestyle is believed to be a significant contributor to lower back pain for this reason.7

Another study found the possible contribution to pain reduction resulting from endorphin release because the people were very connected with themselves and the instructor in a family-like setting (bonding of the group and endorphin release). People find pleasure.8

Additional considerations

The strengths of the study were consistency in data collection and the conduction of the course. Specifically, all measurements were performed by the same person in the same manner at each collection session, assuring consistency in data collection. Also, each week the master teacher was conducting the course. Additional instructors assisted but did not teach participants in different, unsupervised ways, and therefore, exercises were taught the same.

The study was designed within budgetary and other considerations to be a pilot (impact) study to explore the potential efficacy of this new system. Consequently, there were concomitant, inherent limitations: there was inconsistency in group participation and issues with retention. The group started with more participants, but as the study was continued, some withdrew from the program or missed data collection sessions. This resulted in smaller group sizes and, subsequently, in less data being collected.

Participants filled out a Waver Form on which they indicated they were not receiving any medical treatment and were not taking any medication during the study period, with one exception: One person indicated taking medication for high blood pressure.

The Painless Flexibility™ system has a high utility, it is safe and cost-effective. The exercises can be done at home during the leisure time of the participant. These exercises can also be adapted to the individual’s level of experience and flexibility, making it a safe and effective program for anyone experiencing chronic lower back pain and wanting to try an alternative treatment modality.

Conclusion

Chronic back pain reduces quality of life, hinders activities of daily living, and impacts psychological well-being. In a small cohort of adults with chronic back pain, the Painless Flexibility™ program improved the range of motion of all individuals over the course of 18 weeks while also decreasing their pain. The study indicates the efficacy and the potential of this system to be a viable resolution for the common back pain.

Disclosures

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Laszlo Nemeth developed the Painless Flexibility™ system and taught the classes during the study, but had no access to the data and no involvement or influence on the evaluation. He owns the trademark of Painless Flexibility™, the copyright of the exercises and lesson plans.

None of the other authors have any potential conflict of interest.

References

- Gordon R, & Bloxham S: A systematic review of the effects of exercise and physical activity on non-specific chronic low back pain. Healthcare, 4(2): 22. doi:10.3390/healthcare4020022, 2016

- Raichlen, D. A., Pontzer, H., Harris, J. A., Mabulla, A. Z. P., Marlowe, F. W., Snodgrass, J. J, Eick, G., Berbesque, J. C., Sancilio, A., Wood, B. M: Physical activity patterns and biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk in hunter-gatherers, American Journal of Human Biology, Volume 29, Issue 2 https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22919, 2016, (Last accessed on 10/17/2024)

- Giumberteau, JC: Strolling under the skin. 2007, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eW0lvOVKDxE, (Last accessed on 10/17/2024)

- Giumberteau, JC: Muscle Attitudes. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QjMpaRfjOmc, 2010, (Last accessed on 10/17/2024)

- Langevin H: The “New Organ” in the news: Is it real and what does it mean. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ygUvpADY0jo, 2018, (Last accessed on 10/17/2024)

- Khalil, T. M., Asfour, S. S., Martinez, L. M., Waly, S. M., Rosomoff, R. S., & Rosomoff, H. L: Stretching in the rehabilitation of low-back pain patients. Spine, 17(3), 311–317. https://doi.org/10.1097/00007632-199203000-00012, 1992, (Last accessed on 10/17/2024)

- Bordoni, B., & Zanier, E: Clinical and symptomatological reflections: the fascial system. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 7, 401–411. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S68308, 2014

- Dfarhud, D., Malmir, M., & Khanahmadi, M: Happiness & Health: The Biological Factors- Systematic Review Article. Iranian Journal of Public Health, 43(11), 1468–1477, 2014